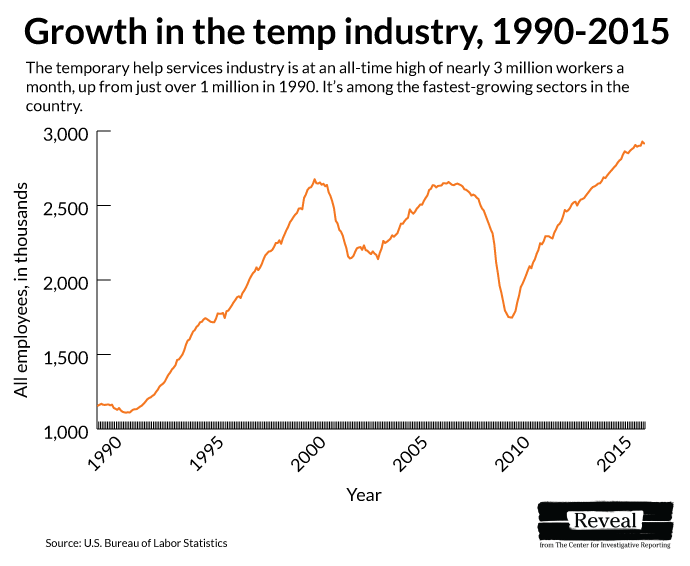

The temp industry is among the fastest-growing sectors of America’s labor market, employing nearly 3 million workers per month in industries such as telecommunications, construction, data processing and more.

Yet the surge in demand has brought with it an epidemic of illegal discrimination, experts and former employees say. Our latest investigation found that when companies asked temp agencies to categorize workers based on race, sex or age, many were more than happy to oblige.

Often, the practice was carried out with code words. Sometimes, the discrimination was more overt. One former recruiter in the Memphis, Tennessee, office of Automation Personnel Services, an industry leader at the heart of our investigation, said her branch manager expressly forbade her from hiring black workers.

Top federal regulators acknowledge that discrimination within the temp industry is a growing problem. But as a large body of reporting and academic research shows, it’s just one issue in a troubling constellation of them.

The temp industry rose with exploited gender bias.

Between the 1940s and ’60s, a small collection of temp agencies rose to prominence – and largely evaded labor unions’ scrutiny – by framing their services as women’s work. In the mid ’40s, when William Russell Kelly founded Russell Kelly Office Service (later renamed Kelly Girl Service, then Kelly Services), he had three employees, 12 customers and $848 in sales. Fifteen years later, when the company went public, it boasted 148 branches and $24 million in sales. That’s a little more than 28,300 percent growth – not bad for a company ostensibly founded to accommodate young wives bored with keeping house.

Scholars such as Erin Hatton have argued that the temp world’s female-centered rise had antilabor undertones. The “Kelly Girl strategy was clever (and successful) because it exploited the era’s cultural ambivalence about white, middle-class women working outside the home,” Hatton wrote in a New York Times op-ed. “Protected by the era’s gender biases, early temp leaders … established a new sector of low-wage, unreliable work right under the noses of powerful labor unions.”

Temps are more likely to get hurt and more likely to wait for medical care.

Temp workers in California and Florida had a 50 percent greater risk of being injured on the job than permanent employees, according to a 2013 investigation by ProPublica. In Oregon, the risk was 66 percent higher. And in Minnesota, it ballooned to 72 percent. Meanwhile, a 2010 study found that temps have “higher claims incidence rates than those in standard employment arrangements” – and that “ratios are twofold higher in the construction and manufacturing industry sectors.”

ProPublica also found that certain incidents play out repeatedly: Workers asphyxiated while cleaning chemical tanks, had limbs caught in tire shredders and other machinery and suffered heat stroke from lengthy periods of sun exposure. Following accidents such as these, companies and temp agencies sometimes would bicker over which party was liable, delaying emergency services.

Temp work helps breed income inequality.

The temp industry is growing quickly and shows few signs of slowing. In fact, by 2022, the employment services industry (which includes temporary help services) is projected to expand from about 3 million workers a month to almost 4 million a month, according to a 2013 report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But temp work often is low paid; sometimes it’s even abusive. A recent study published in The Journal of Labor and Society found that several agencies in New Jersey “engage in wage theft, violate overtime law, charge exorbitant fees, and prevent workers from using unemployment insurance or workers’ compensation.” And because temps across the country reportedly make 25 percent less than permanent employees on average, their rank-and-file growth actually might play a role in exacerbating America’s wage gap. In other words: As the temp workforce grows, inequality grows alongside it.

What’s being done to combat these problems?

Some workers are pushing back. On Dec. 21, workers in Chicago were awarded $1.5 million after a court determined that a labor company and a second now-defunct one were “complying with a discriminatory request” designed to exclude African Americans.

In September, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that companies that use temps now are considered “joint employers.” As a result, a partner at one prominent labor law firm recently advised potential employers that “you have to look at temporary employees as essentially the same as your employees.”

We’ll continue to explore the many faces of workplace discrimination throughout the year and will stay on top of developments in the temp industry. If you’ve had experience with discrimination on the job that you’d like to share, you can tell us about it here. Your insights are confidential and could help inform our ongoing reporting.